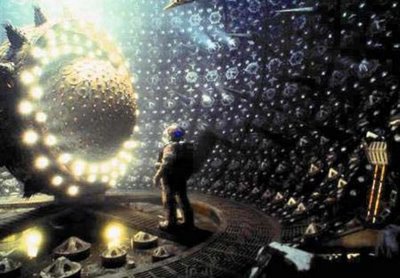

Splatter Cinema presents TOTAL RECALL (1990); Dir. Paul Verhoeven; Starring Arnold Schwarzenegger, Sharon Stone, Ronny Cox and Michael Ironside; Tuesday, June 11 @ 9:30 p,m.; Plaza Theatre; Trailer here.

Splatter Cinema presents TOTAL RECALL (1990); Dir. Paul Verhoeven; Starring Arnold Schwarzenegger, Sharon Stone, Ronny Cox and Michael Ironside; Tuesday, June 11 @ 9:30 p,m.; Plaza Theatre; Trailer here.

By Robert Emmett Murphy

Contributing Writer

TOTAL RECALL, released at the dawn of the new decade of the 1990s, is without a doubt the capstone of the SF film aesthetic of the decade it was leaving behind. It is also one of the finest of the Arnold Schwarzenegger vehicles and earned the distinction of being, up to that point, one of the most expensive, and profitable, films ever made. Just the next year, another Arnie flick, TERMINATOR 2: JUDGEMENT DAY, would define the aesthetic of the coming decade, and dwarf both TOTAL RECALL’s $60 million dollar budget and $260 million worldwide gross.

Paired, these two films represent remarkable transitional pieces, demonstrated in how they pushed the then-contemporary limits in FX technologies. TOTAL RECALL’s special makeup effects were by Rob Bottin, and its visual effects by Eric Brevig. Their labor represents very nearly the last mega-budget efforts of techniques and technologies about to be made obsolete when computer graphics (only nominally represented in this film) took over the whole industry. They were eye-popping at the time, but somewhat rubber and plastic looking now. T2, with the silver-liquid-metal killer robot, was the fist masterpiece of the revolution. Though CG made the canvas of what could be realized, and how well it could be realized, almost infinitely larger, if you leave the new tech’s masterpieces aside, there’s no doubt that a rubbery solid has a more real feel than today’s most-often-run-of-the-mill pixelation.

Both films also pushed the boundaries of narrative sophistication allowed in the escapist. T2 is undeniably the greater of the two, featuring richer characterization, a more complex plot with fewer loopholes, and more maturity in its take on a shared anti-authoritarian credo. T2 didn’t asset that our dependency on the maintenance of systems and hierarchies were injustices in-of-themselves and didn’t embrace the ideology of scarcity-as-myth. It recognized that the motives of those who commit (often inadvertent) harm often have legitimacy, nor did it deny the reality of the imperfectness in conduct of even the good guys. Yet TOTAL RECALL, so richly cheesy, so lavishly textureless (except the slick texture of spraying blood), and so deeply, morally corrupt in such a friendly, innocent way, is the better time-capsule of the society that produced it.

The Schwarenegger Effect and a Passion for Perversity

As an actor, Arnie was beloved by directors who wanted an appealing hero embodied in someone who wouldn’t distract from visual ideas by creating inappropriately humanistic identities. He was perfectly matched with TERMINATOR director James Cameron, but even more so here with Paul Verhoeven. I should make it clear, though, that Arnie hired Verhoeven, not the other way around. Arnie bought the rights after the film had languished in production hell for almost 15 years. Still, clearly his casting of himself was a defter choice than other, better, actors who’d been considered like Richard Dreyfuss and William Hurt (to say nothing of Patrick Swayze). Of course, those actors would’ve been cast in much different versions of the script, which had been rewritten some 40 times. Reportedly the final version was very close to the first version, while all those in-between had strayed into inappropriate attempts at distracting psychological depth.

Quaid/Hauser (Arnold Schwarzenegger) takes a ride in a Johnny Cab in TOTAL RECALL. TriStar Pictures, 1990.

Both Verhoeven and Cameron have demonstrated a passion for the SF genre and world-building detail (my favorite in TOTAL RECALL was the Johnny Cabs, which even in 1990 provided a charming anachronistic poke at what the future likely won’t be). They also share a flair for offhanded satire and sleekly complex executions of muscular action scenes. However, Verhoeven had something Cameron lacked – a penchant for perversity. Perversity is what Arnie’s films always seemed to want to wallow in but were generally too timid to indulge. In T2, Cameron’s only perversity was to make the most violent pacifist film in history. TOTAL RECALL is much more deeply, cooly, sicko.

To call the violence gratuitous is like calling water wet, but Verhoeven showed a gift for an over-the-top comic-book harmlessness that camouflaged all but a whiff of the film’s obsessive sadism. He’d done it before, with ROBOCOP, but the movie was more serious-minded, more humanistic, and modestly more restrained. He did it after, in STARSHIP TROOPERS, but that film demanded something more serious-minded and humanistic than Verhoeven could pull off that week, so the balance was thrown off. TROOPERS ended up seeming uglier and meaner than this film, even though if you’re actually paying attention to its moral underpinnings, TOTAL RECALL should’ve been the more condemnable. TOTAL RECALL’s ability to make such unrestrained venality seem man-child-friendly is probably why it’s the most fondly remembered of the three (that, and it wasn’t demeaned by crappy sequels, but I’ll come back to the whole story behind that later).

Misty Watercolor Memories of the Way We Weren’t

Arnie plays the improbable everyman, Douglas Quaid – who has too good a body, with too breathtakingly beautiful a wife, too fabulous an apartment, in too clean a city – to be what we are told he is: a construction worker. But he’s dissatisfied and distracted by vivid dreams of the planet Mars, so he goes to the movies and watches a fantasy about a James-Bond-type secret agent on the Red Planet. Except that this is the future, and instead of passively sitting in theater seats as we sad contemporaries do, he goes to the offices of Rekal Inc. and purchases elaborate fictional memories that are implanted in his head, so he can experience the fantasy as if it were real.

As they said on the poster to another SF classic, and nothing can go wrong…go wrong…go wrong…

Nothing except maybe the fictional memories are too similar to real ones that have been deliberately, artificially, locked somewhere in Quaid’s subconscious where he can’t get them. The entertainment technology partially opens the doors of perception, and Quaid is now in touch with another identity, a real-but-forgotten self named Hauser, who actually is a James-Bond-type secret agent. Now that Quaid’s somewhat awake, of course, the bad guys want him dead. Quaid, the innocent, receives prerecorded instructions from his alter-self Hauser, and actually makes the trip to Mars to discover the truth about his identity and the conspiracy in which he’s all wrapped up.

Or alternately, Quaid’s still in the fantasy, suffering from something called a schizoid embolism, and the longer he plays out the fantasy scenario, the harder it will be to get back to the real world.

A Short and Clever Tale by Philip K. Dick Gets Bigger, Bolder

TOTAL RECALL is a loose adaptation of Philip K. Dick’s short story, “We Can Remember It for You Wholesale.” It preserves Dick’s main themes remarkably well, but in making a bigger, bolder, epic out of the short and clever tale, it shifts emphasis. Both film and story have great fun with the “is-it-real-or-is-it-not?” theme, but the always tortured Dick was more interested in the vulnerability and terror of middle-ground between the two, while here the script writers (there were five, but primarily Ronald Shusett and Dan O’Bannon) and even more Verhoeven, focus on a he-man liberation from all moral constraints that only a wholly invented world can secure. The first terrible revelation to our hero comes when his wife admits she never really loved him, saying: “Sorry Quaid, your whole life is just a dream.” But in truth, he really doesn’t start enjoying himself until the curtains fall on that reality, as lifted on the newer, nastier, one.

Most of Verhoeven’s films speak of a man who longs for such a venue. ROBOCOP is the only one I can think of that was convincingly moralistic; most don’t even try. His cynicism about human nature is demonstrated even before the plot gets rolling. There’s a scene where Quaid’s impossibly beautiful wife, Lori (Sharon Stone) is coming on to him, kissing him and literally climbing on top of him, but he can’t take his eyes off the TV news. He’s mesmerized by a politely fanatical speech by Vilos Cohaagen (Ronny Cox), Mars’ wicked, corporate, planetary emperor, who is condemning a violent insurrection by vile mutants on Mars. It’s a typical Verhoeven scene, with no faith in love or relationship and insisting that all our familiar pleasures will become insufferable because of their familiarity, that we are constantly driven to the edge by our desire for newer, more terrible sensations.

Divorce TOTAL RECALL-style. Sharon Stone and Arnold Schwarzenegger in TOTAL RECALL. TriStar Pictures, 1990.

There’s also a lot of foreshadowing in this scene. Quaid’s distraction is honest, but Lori’s bitch-in-heat behavior is as fake as a whore’s orgasm, which, in a very convoluted way, it will turn out to be exactly what she is.We’ll also soon learn that everything is really about Cohaagen.

Verhoeven’s politics are disingenuously leftist and perfectly in tune with the twilight of Reaganism. Though the real-world Arnie would eventually become the wholly incompetent Republican Governor of California, his fictional counterpart would prove to be a liberator of the proletariat from the shackles of capitalism and display such a soulless penchant for terrorististic, mass-murdering virtue that he makes Che Guevara look like Mitt Romney. However, while the film’s manifesto is anti-corporate-hegemony and pro-labor, its heart is materialistic and misogynistic, an ideology where sex means nothing without dominating power, and dominating power isn’t sexy unless it’s brutally corrupt.

A mere 12 months later, when Arnie would return in T2, we were already in a more innocent era, anticipating Bill Clinton and a decade so honest, sincere, and without sin that even something as trivial as a blow-job could blow-up into a constitutional crisis.

Sophisticated SF Narrative Vs. Special Effects

The script of TOTAL RECALL is remarkably information dense. Though almost every shot seems to embody some sort of special effect, smart writing trumps the spectacle in many places. In several instances, characters get trapped outside Mars’ artificial environments, and the so-thin-it-is-almost-non-existent Martian atmosphere does the predictable nastiness to their bodies (predictable, but not especially scientifically accurate). These scenes featured eye-bulging, artery-bursting, FX dummies that were just plain silly-looking. On the other hand, in a dialogue-driven scene, Dr. Edgemar (Roy Brocksmith) tries to talk Quaid down from his delusion (“You’re not here, and neither am I”) – unless it’s not a delusion and the good doctor is trying to poison him. That scene proves to be one of the high points of the film.

And the narrative evolves in a sophisticated way, changing venues and accumulating characters that set motivation on a path of constant evolution. Quaid starts only wanting to know who he really is and how to stay alive. This quest leads him into a situation where he needs to take on the mantel of the leader of the revolution. Cohaagen’s abuse of workers in Mars’ artificial environments has produced a spectacular underclass of weird mutants including dwarves, co-joined twins, those disfigured by tumors, those sporting extra-limbs, the telepathic, and most memorably a whore named Mary (more about her later). Quaid will forget self-preservation and fight to end Cohaagen’s monopoly over resources that should be shared collectively by these huddled masses. Each step towards messianic-pseudo-Marxist-leadership is also a step closer to the secrets of his forgotten identity.

Without doubt, Verhoeven can do plot. It’s appropriately twisty, or as another review put it, “There are so many of them, you could probably miss one or two and grab another box of popcorn.” But Verhoeven skillfully avoids tripping over his own threads.

Strong Casting for a Sci-Fi Film

Verhoeven is slick – but not without thought; soulless – but not without character. In fact, Verhoeven has a fine track record of drawing strong performances from actors playing very artificial parts. Arnold Schwarzenegger is the case in point. Never an accomplished actor, he rarely did more than use jokes to cover his inability to emote, but he still had tremendous screen presence. He could sell a Superman the way more talented thespians couldn’t. Here, almost shockingly, he even displays a very modest hint of semi-nuance that is lacking in any of his other roles except, well, T2. Underneath his “Superman” persona, he’s confused and frightened and vulnerable, a man betrayed by the structure of reality itself. “Who da hell em I?” says Quaid in a thick, heart-tugging, unaffected accent.

It helps that the rest of the cast is so very strong.

Sharon Stone’s film career was already a decade old at this point, meaning that it was very likely nearing its end since her primary selling points were that she was beautiful and blonde. Though in IRRECONCILABLE DIFFERENCES (1984), she demonstrated she was a gifted comic actress, no one seemed to notice, and she couldn’t elevate herself out of B (or C) movies and TV mediocrity. Here, her role was not only small, but exploitive and nasty – a lying lynx who offers sex, then tries to kill, then comes back an hour later and tries to kill again, gets in a cat-fight with another sexy whore, then gets dead. Yet absolutely every man was blown away by her ice-cold, predatory athleticism and tight-fitting and barely present wardrobe.

Verhoeven, who likes to use the same people both in front and behind the camera in film after film (TOTAL RECALL is ripe with ROBOCOP alumni) later gave her the lead in BASIC INSTINCT (1992), which was even sicker than this puppy, and overnight she achieved her long overdue super-stardom. She’d leave roles like this behind quickly (and in the process garner 13 awards and 20 nominations, including an Oscar nod), but there was a moment when she was the definition of the Hollywood Ice-Princess reborn and that moment started here.

Kickass Melina (Rachel Ticothin) is far better suited to Arnold Schwarenegger's action hero in TOTAL RECALL. TriStar Pictures, 1990.

Rachel Ticotin played Melina, the female romantic lead and other participant in the hot-and-bothered cat-fight with Sharon Stone. Her prescription, per the “Rekal” fantasy that Quaid dictated in the film’s opening scenes, was to be “dark-haired, athletic, sleazy and demure.” She pulled it off perfectly, notably being convincing while speaking the most lunatic romantic dialogue in history. In her first scene, she grabs Quaid’s crotch and hisses, “What have you been feeding this?” To which Quaid, more Hauser by the minute, quips, “Blondes.” Her luminous smile in response is as close to true love as you’ll ever see in a Verhoeven film. Up to a point, she’s as a perfect Verhoeven girl as Stone, one part empowered/two parts vice/seven parts objectified. But unlike Stone, he won’t use her again, possibly because she comes off a few degrees more real, and many times more street, than Stone’s (then) Ice-Princess persona. Perhaps she was not quite artificial enough for Verhoeven’s exquisitely surfacy aesthetics.

Ronny Cox wasn’t the first choice for Cohaagen. It was offered to Kurtwood Smith, who, with Cox, played one of the two main villains in ROBOCOP. Though the lion’s share of Cox’s roles are warm, noble and paternalistic, he clearly enjoyed the corporate baddies Verhoeven repeatedly cast him as. In this film, he and Michael Ironside are the two main villains. In obvious deference to Arnie’s acting talents, these two, not the hero, got the film’s few dramatic scenes.

Neat Ideas and Savage Candy

But enough about human talent in a film so inhumane, TOTAL RECALL was all about neat ideas and savage candy. The highlights:

- In a plot point early on,Quaid has a tracking device in his head. The recorded Hauser tells him how to remove it – Reach into your nose with tweezers and pull really hard and really painfully. Rated high on the ICK! Factor.

- There are endless, loud shoot-outs with big-assed automatic weapons plus explosives, both inappropriate choices in a pressurized environment. These conflicts justified the frequency of sucking people into the Martian near-vacuum which then justified the close-ups of the forementioned, eye-bulging, rubber FX dummies. It also justified the extreme body count; one review counted (yes, some reviewers sit in front of their TVs and actually count this stuff) 77 dead bad guys. And that’s onlythe bad guys. The film showed rare indifference to the lives of innocent bystanders. It likely had an even higher collateral damage rate than the invasions of Grenada and Panama combined. The most memorable of these was during a shootout on an escalator, when cornered Arnie grabs some poor, random, commuter and uses him as a human shield. That guy gets reduced to Swiss cheese, and Arnie goes off to continue his one-man-war against wicked corporatism

- Literally the only female in the film who is not a whore is a disgustingly obese tourist arriving at the Mars Spaceport inanely saying “Two weeks” over and over. Except she isn’t even a woman, but a cybernetic fat suit that malfunctions. In the eyeball-kick heavy film, the single best effect is the costume coming apart like a high-tech flower blossoming, revealing Quaid beneath. Quaid then throws the lady-head at a cop. The head speaks a snappy line and explodes, killing at least three people.

- The dispatching of Sharon Stone is the stuff of woman-despising-legend. After Ms. Stone engages in three fights in five minutes, she’s prone helplessly before Arnie and pleading for her life. “We’re married,” she says. Arnie snickers, “Conseeder dis a divorce,” and machine-guns her.

- Arnie has many such bloodthirsty quips. In one scene, he dispatches another friend who betrayed him with a miner’s hydraulic drill to the gut, gleefully shouting, “Screw you!”

-

And let’s not forget Lycia Naff, who has the smallest of parts, but secured much of the film’s fame. She played a whore (what else) named Mary who was in only two scenes, totaling less than four lines of dialogue, and exposed her breasts to strangers both times. Yet ask any man who was an adolescent in 1990 if he remembers the film, and he’ll no doubt answer, “Yeah, that’s the one with the chick with three boobies.” (If you watch the DVD version, don’t miss out on the commentary track where Verhoeven nobly attempts to intellectualize the triceratits). Mary is killed by Michael Ironside’s character Richter in a manner that is both callous and sexually demeaning.

- Richter gets his comeuppance in a fistfight on an elevator platform. He loses his balance, falls, saves himself by grabbing the edge—until the platform rises to the next floor, cutting both of his arms off, leaving his forearms with Arnie as souvenirs. And of course, the noble hero calls to the falling man, “See you at the party, Richter!”

And I should say, this is only the sickness we got AFTER the film was cut to avoid an X-Rating. God knows what the unrestrained version looked like.

All this mayhem and no real people does eventually take its toll. There’s no denying the last third is warmed-over and derivative. For a movie that had delivered so many surprises both in plot and inventive detail, the routine conclusion is banal, protracted, idiocy. Arnie/Quaid/Hauser’s saving all the good people of the planet is logically feasible only to some schmuck who also ascribes to Young-Earth Creationism. But if you pay close attention though the explosions and thunderous score (by Jerry Goldsmith, who considers it one of his personal favorites), plenty of clues suggest on which side over the what-is-reality fence you should be standing and that the seeming dopiness of the last several minutes might actually be meta-fiction Easter egging.

The Sequel That Never Was or Was It? And the Remake That Shouldn’t Have Been

TOTAL RECALL grossed almost 100 million over budget outlay, so why wasn’t there a sequel? Well…

There was supposed to be. The idea was to take another Dick story as the launching point and tell the tale of Quaid getting in trouble with authorities again. You see, properly integrated in society, those telepathic mutants are useful. They can bring down the homicide rate by solving crimes and punishing the guilty before the killing even takes place.

Does this plot sound somewhat familiar?

Does this plot sound somewhat familiar?

With Verhoeven returning to the Netherlands after a string of commercial disappointments (starting with 1995’s SHOWGIRLS, perhaps the most sexually exploitive and misogynistic feminist film in history) and Arnie entering politics by the end of that decade, the project proceeded without them. It mutated into something unrecognizable and was released in 2004 as MINORITY REPORT. The script by Scott Frank and Jon Cohen was tight and hugely ambitious, the film was beautifully directed by Steven Spielberg, and Tom Cruise is simply a more talented lead. Yet the greater film did not burn into our collective memory the way TOTAL RECALL did.

TOTAL RECALL’s place in our culture was probably additionally secured by how it towered over its ill-conceived remake of last year. That stared Colin Farrell who is clearly a better actor than Arnie, but does not have as much charisma. Overall the characterization is flatter than the original, odd given how the original was almost smug about its lack of character depth. This new movie sold itself as “darker,” but that wasn’t really accurate. What they really meant to say was that it was humorless, and the violence, now mostly committed against robots, was heavily sanitized. The politics in the original was disingenuous, but also bolder in its relationship to real-world class conflict. In the remake, the good-guys vs bad-guys is a more nationalistic battle modeled on the aggressive wars of 19th century imperialism and Australia’s struggles with the British Commonwealth; thus it is far more nostalgic and far less provocative. It’s also wholly Earth-bound, losing the original story’s dreams of Mars and the first film’s Mars locations. The remake also ditches every single mutant except the “chick with three boobies,” who now has little explanation for being there. No aliens either – I didn’t mention them above, but aliens were important in both the original story and the first film. The $125 million dollar budget, adjusted for inflation, was really not much more than the 1990 release, but the movie grossed a mere $199 million, or less than half the original film’s inflation-adjusted business.

Robert Emmett Murphy Jr. is 47 years old and lives in New York City. Formerly employed, he now has plenty of time to write about movies and books and play with his cats.