Video may have killed the radio star, or so that ’80s song goes, but it launched a lifelong passion for cult action movies in Kool Kat of the Week Mike Malloy. Now he’s paying homage to the format that revolutionized the way people accessed and watched movies from the late 1970s to the 1990s in the documentary series PLASTIC MOVIES REWOUND: THE STORY OF THE ’80S HOME VIDEO BOOM, for which he is seeking funding through a Kickstarter campaign. The timing couldn’t be more perfect with VHS tapes, like 33rpm LPs, enjoying a renaissance among collectors, both old and new.

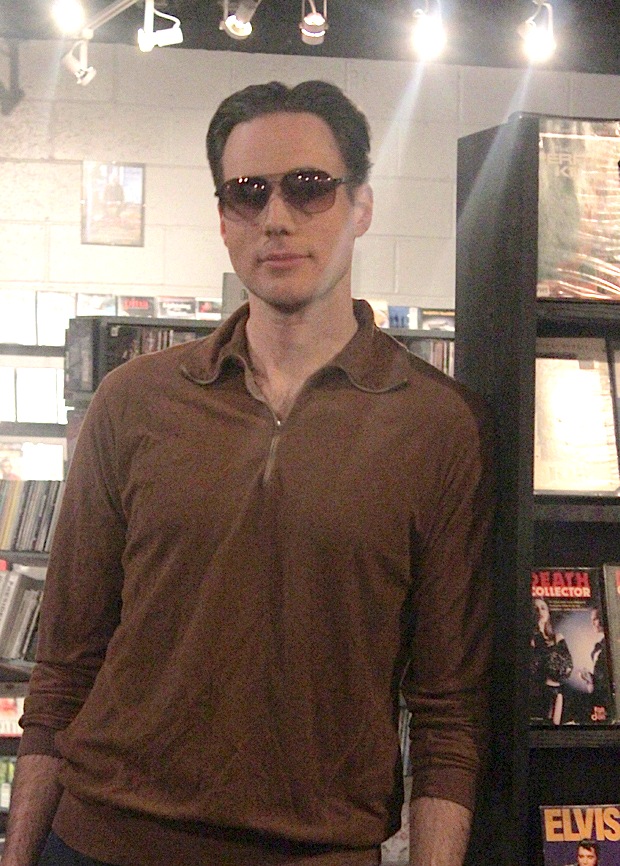

From his slicked-back hair to his Retro bowling shirts, Mike looks like he ought to be playing the stand-up bass in a rockabilly band. Instead he’s devoted himself to “playing” tribute to a side of cinema that often doesn’t get a lot of love from mainstream critics. At age 19, he signed his first book contract to write the first published biography of Spaghetti Western star Lee Van Cleef (for McFarland & Co.) Since then, he went on to write articles for a wide spectrum of national film magazines, served as managing editor of fan favorite Cult Movies Magazine, has spoken about movie topics at universities, ghost-wrote several fim books, and served on the selection committee of the 2006 Atlanta Film Festival.

In the past few years, Mike has moved increasingly both in front of and behind the camera. He has acted in more than 25 features and shorts. He co-produced the Western THE SCARLET WORM (2011) and directed the short, LOOK OUT! IT’S GOING TO BLOW! (2006), which won the award for best comedy short at MicroCineFest in Baltimore. But he’s garnered the most acclaim, both national and international, for EUROCRIME! THE ITALIAN COP AND GANGSTER FILMS THAT RULED THE ’70s, a kickass documentary homage to that B-movie subgenre which he wrote, directed, edited and produced.

ATLRetro caught up with Mike recently to find out more about how home videos fired his fascination with film, his unique vision for PLASTIC MOVIES REWOUND, some really cool incentives he’s lined up for his Kickstarter campaign which collectors will love and what’s up next for Georgia’s Renaissance man of cult action cinema.

ATLRetro caught up with Mike recently to find out more about how home videos fired his fascination with film, his unique vision for PLASTIC MOVIES REWOUND, some really cool incentives he’s lined up for his Kickstarter campaign which collectors will love and what’s up next for Georgia’s Renaissance man of cult action cinema.

Having written Lee Van Cleef‘s first published biography at age 19, you’ve obviously been into rare cult and B movies since an early age. What triggered your passion for the less reputable side of cinema and why does it appeal to you so much?

I’m a rare guy who’s deep into cult and genre cinema without caring much for horror or anything fantastic. For me, it’s all about a desperate Warren Oates shooting it out in Mexico. Or Lee Marvin with a submachine gun. For some reason, I’m just drawn to gritty tough-guy cinema – which is not necessarily the same thing as action cinema.

How did the home video revolution influence you personally? Having been born in 1976, you can’t really remember the pre-video days, I’d guess, but it must have afforded you access to a whole spectrum of these movies which otherwise would have been hard to track down and see.

And I even missed most of the ’80s video boom, because my parents, in 1990, were the last on the block to get a VCR. But in 1994, I made up for lost time. I had a college girlfriend who had an off-campus apartment, and while she was at work, she didn’t like the idea of me being on campus, potentially fraternizing with other young ladies. So before each shift, she would take me by the local mom-and-pop vid store and rent me 8 hours’ worth of Bronson, Van Cleef, Carradine, etc. That kept me safely in her apartment, and it put me on the cinema path I’m on.

In Atlanta, Videodrome seems to be the last independent rental retailer still in business and it’s even hard to find a Blockbuster left. And of course, they now just stock DVDs. Now you can order up a movie online and watch it instantly. Do you think we’ve lost something by no longer going in to browse, and was there a particular video store that became your home away from home?

One of our interviewees said something interesting: The mom-and-pop video store business model was based on customer DISsatisfaction. That is, you’d go in to rent CITIZEN KANE, it would be checked out, and you’d somehow end up leaving with SHRIEK OF THE MUTILATED (1974). Being forced to browse leads to an experimental attitude in movie watching. That’s a good thing.

VHS tapes can get damaged easily, the picture and sound quality can’t compare to a bluRay (or often even a regular DVD) and they rarely show a movie in widescreen. Why be nostalgic about them, and is it true that the VHS format, like LPs, is having a comeback?

VHS is experiencing a major comeback. There are about 20 little startup companies that have begun releasing movies to VHS again. A certain old horror VHS – of a film called DEMON QUEEN (1986) – sold recently on eBay for $750.00. VHS conventions are springing up all over the country.

I’ve always thought that the format is superior for horror films. If you watch THE TEXAS CHAIN SAW MASSACRE (1974) on a soft old VHS poorly transferred from a faded film print, that makes you feel as if you’re watching some underground snuff film obtained from a shady guy in a trench coat. Watch that same movie on a pristine Blu-Ray, and you don’t get that same grimy feeling.

There have been other documentaries about home video, such as ADJUST YOUR TRACKING (2013) and REWIND THIS (2013). What will PLASTIC MOVIES REWOUND add to the topic that hasn’t been covered already?

PLASTIC MOVIES REWOUND will be a three-hour series, spanning six half-hour episodes. Those others just have a feature-length running time. So if mine isn’t the most definitive word on the subject, I’ve really screwed up. I’m sort of glad those docs exist as companion works, because it frees me up to explore some of the weirder corners of the phenomenon I find fascinating. Things like video vending machines and pizza-style home delivery of VHS tapes.

You’ve got a pretty interesting line-up of interviewees, not all of which are big names. Can you tell us about a few of them and how you went about selecting them.

Right, many of these people are very significant without being instantly recognizable. We have Mitch Lowe, the founder of Netflix (and later a CEO of Redbox). We have Jim Olenski, owner of what is considered to be the first-ever video store. We have Seth Willenson, a Vice President at RCA who oversaw their failed video disc format. That’s just several off the top of my head. They all have that level of significance. And we interviewed a bunch of cult filmmakers, because working at the cheap extreme of the video boom was where some of the craziest stories were. Further, we were glad – er, glad/sad – to have been able to document a closing video store in Toronto during its final month.

Moviemakers, and artists of all ilk, have always seemingly been ripped off by others who pocket all the money. What distinguishes the video era in that regard, and are there any lessons filmmakers can apply to the current wild west of digital camerawork and online distribution?

I think the potential for ripping off artists is greater when an industry is in upheaval, when the rules and the financial models are unclear. And you’re right, VOD and streaming have caused the same type of upheaval that the videocassette did in its day. So I love all the anecdotes we captured of swindled ’80s filmmakers fighting back against their underhanded distributors. And I hope today’s filmmakers realize that distributors are now becoming largely unnecessary at all. For instance, I hope Vimeo OnDemand – with its 90-10 split in favor of the filmmaker – is a total game changer.

You obviously went into this project with a lot of background, but did you find out any big surprises or delightful unexpected moments during your interviews/research?

I went into the project feeling proud that I was going to cover not only VHS and Beta, but all the failed video formats – like Cartrivision, Selectavision (CED) and V-Cord II. Turns out, they were just the tip of the iceberg. I now probably have about 15 different also-ran video formats I can touch on.

How different would the world be today if Cartrivision had caught on instead of VHS?

Well, Cartrivision was an early attempt at rights management for movies. The Cartrivision rental tapes couldn’t be rewound at home; that could only be done at Sears, where you rented them. It limited you to one viewing per rental. So it would’ve started the concept of video rentals off on a very different attitude and philosophy. I think part of the reason the ’80s home video phenomenon was such a boom was the freedom associated with it – you could rent a movie of your choosing and watch it at a time of your choosing. You could watch it a number of times before returning. Hell, you could use your rewind button to watch a jugsy shower scene over and over.

Tell us about the Kickstarter campaign. How’s it going and how are you going to use the monies raised to finalize the film?

Since ADJUST YOUR TRACKING and REWIND THIS both successfully kickstarted, I knew this would be an uphill battle. My only chance was to turn what is normally a beg-a-thon into a reward-a-thon. So I created a $75 level for the collectors where they could get so much more than just a copy of the documentary. The very first expense I’ll cover, if I get successfully funded, will be an 8 terabyte hard drive. I really can’t cut another frame until I get it.

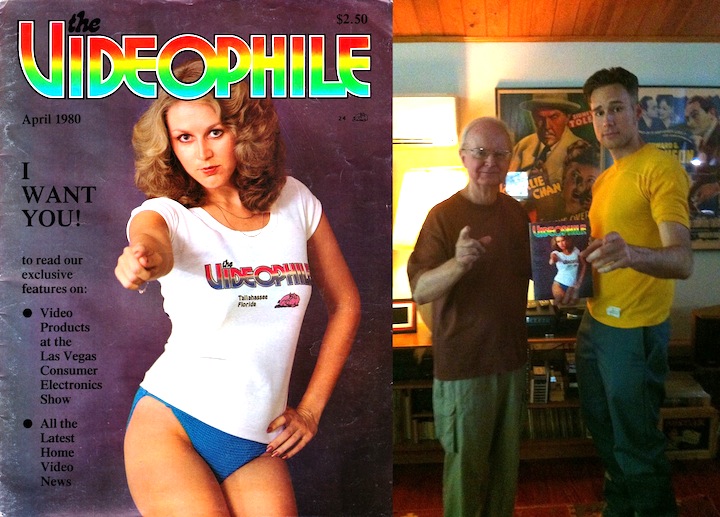

You’ve got some mighty cool incentives for donors, including actual vintage VHS cassettes. Tell us a little bit about them.

Not only have many of our filmmaker interviewees donated signed VHS and DVDs of their movies (to say nothing of rare, unused artwork and such), but a lot of these new startup VHS companies have also donated rewards. I’m feeling very supported.

Anything else on your plate right now or next as a writer, director, producer or actor?

Later this year, I’m acting in HOT LEAD, HARD FURY in Denver and BUBBA THE REDNECK WEREWOLF in Florida. I wish someone would cast me locally so my pay doesn’t keep getting eaten up by travel expenses!

Editor’s Note: All photos are courtesy of Mike Malloy and used with permission.