By Robert Emmett Murphy Jr.

By Robert Emmett Murphy Jr.

Special to ATLRetro.com

Orson Welles’ WAR OF THE WORLDS radio broadcast (1938), the most famous of all media hoaxes, was, in fact, not a hoax at all.

It starts, 40 years before the incident, with the publication of H.G.Wells’ novel WAR OF THE WORLDS (1898), which was almost the first – and certainly the earliest that is still influential – science fiction novel of alien invasion. It was part of a larger genre of “Invasion literature,” a body of proto-SF novels concerning England being invaded by its more familiar enemies, generally the Germans. The other Invasion novels tended to be propagandist to the point of jingoism, and Wells, who always was internally torn regarding the subject of militarism, chose to deconstruct the literature. It is almost, but not quite, an anti-war novel. Though it featured feats of great heroism by the English military, it devoted significant real estate to human hypocrisies, cowardice and cravenness. It challenged the nationalistic/colonial myths that drove most other Invasion novels.

Wells told his tale with potent verisimilitude, using real and exactly contemporary settings, and employed literary devices like its first person narrator addressing the reader directly as if he’s discussing events familiar to all: “It is curious to recall some of the mental habits of those departed days…The storm burst upon us six years ago now.” He referenced other sources when there were story details that the narrator could not have been expected to have directly witnessed, “As Mars approached opposition, Lavelle of Java [observatory] set the wires of the astronomical exchange palpitating…He compared it to a colossal puff of flame suddenly and violently squirted out of the planet, ‘as flaming gases rushed out of a gun.’…A singularly appropriate phrase it proved. Yet the next day there was nothing of this in the papers except a little note in the Daily Telegraph.” These were effective devices for creating a faux-realism, as it mimicked the style of a history book and the epistolary novel more than the then-evolving fictional narratives of most modern novels written in a close third person POV.

The Mercury Theater must have been drawn Wells’ narrative when they chose this work for their 1938 Halloween-eve broadcast. Another was probably related to [the fact that] Universal Studios had established that Americans had a taste for being scared, but by the late 1930s, their great franchise monsters slipped towards self-parody because folklore-based supernatural thrillers were not the best platform to address what was really scaring America at the time. The rise of fascism played a large role in science fiction replacing supernatural tales as the fantasy of the Zeitgeist.

The cover of a 1970s LP of the broadcast.

In the Mercury Theater version, scriptwriters Howard Koch (CASABLANCA [1942]) and Anne Froelick (HARRIET CRAIG [1950]) used real and exactly contemporary settings, this time in the U.S. and within the range of the New York City broadcast tower. They heightened the immediacy by presenting the first half of the broadcast entirely in the form of faux-news bulletins interrupting “regularly scheduled programing,” which was also fictional. The bulletins came with increasing regularity, then took over the programing entirely as the war turned hot and people started to die. There were emergency response bulletins, casualty figures, evacuation instructions and reports of millions of refugees clogging the roads. A government official makes a statement, and the actor mimicked President Roosevelt’s voice, though the character was given a different name. The story didn’t use the device of real-time, wherein the events of the narrative covered the same length of time as the experience of audience, but the time-compression was deftly disguised. As the audience listened for minutes, they never questioning that hours of story-time had elapsed (or months, if you include the reports of the observations “of the colossal puff of flame suddenly and violently squirted out of the planet” Mars).

As the story moved to its pre-intermission climax, Orson Welles (producer, director, and starring as one of the reporters) claimed to be transmitting a view from the top of a Manhattan skyscraper, and described an apocalyptic scene: “five great machines” wade across the Hudson River to New York City, spewing poison gas. As the smoke drifts from west to east, he can see people “falling over like flies” while others, panicked, dove into the East River “like rats.” Finally, the gas reaches Welles. The last sound is the voice of a desperate ham radio operator, “2X2L calling CQ. Isn’t there anyone on the air? Isn’t there anyone on the air? Isn’t there… anyone?”

A thing about these bold devices, though they have the power to captivate, even overwhelm, the audience, is that they limit options for complex storytelling. The more conventional devices are more flexible, which is why they are used more often and which is how they became conventional in the first place. When the story became more complex and character-driven in the second act, more conventional dialogue and monologue were used. It marked a bold dramatic shift, akin to how innovative and overwhelming the Omaha Beach sequence was in SAVING PRIVATE RYAN (1998), but as that sequence told us very little of the actual plot and specific characters, as soon as audience was properly impressed and completely tamed, and the action moved away from the beach, a far more conventional WWII film unfolded.

Orson Welles performing WAR OF THE WORLDS.

Because of the scandal, the very fine second act is under-appreciated. Especially notable is a sequence where the narrator (again Orson Welles) hides in the basement with a madman. It’s a scene in the book (and I should note that the Mercury Theater version, for all its changes from the original, displayed the most fidelity of any of the major adaptations of Wells’ novel). Mercury revised this sequence to address contemporary concerns. The madman is clearly traumatized by the violence inflicted on his nation, and rants delusionally of taking revenge by creating a cult of personality around himself and training a generation of ruthless warrior children. This was a pretty explicit reference to Europe, traumatized by WWI, falling in goose-step behind fascism. Mercury’s WAR OF THE WORLDS, like H.G. Wells’ WAR OF THE WORLDS, articulates the fears of the coming World War; they just happen to be talking about two different World Wars. The stressing of the poison gas over the heat-rays was another change from the original novel, reflecting that the world had changed since 1898.

The fact that this was a fiction was made clear before the play began, and it was announced again at intermission, and at the end Orson Welles breaks character to state once more this was fiction, “the equivalent of dressing up in a sheet, jumping out of a bush and saying, ‘Boo!’” Yet reportedly more than a million Americans believed it was all true (later attempts to come up with more realistic estimates put the number in the thousands). The not-a-hoax had unleashed THE NIGHT THAT PANICKED AMERICA (a title of a 1975 ABC TV movie that recreated the events).

OK, so what the hell happened?

Well, the Mercury Theater had fairly poor ratings as it was put up against the very popular CHASE AND SANBORN HOUR on NBC radio. About 15 minutes into CHASE AND SANBORN, the first comic sketch ended and a musical number began. Apparently the musicians weren’t that talented and many listeners started “channel flipping” (a truly degenerate cultural pastime that was introduced with the corrupting new technology of radio, and even today has yet to be purged from our civilization). When the listeners hit CBS, they encountered music they liked better, the fictional “regularly scheduled program” of “Ramon Raquello and His Orchestra.” It’s not a surprise they stopped, as it was actually the CBS Orchestra directed by the great Bernard Herrmann (CITIZEN KANE [1941], PSYCHO [1960]). They had missed the opening announcement that this program was fiction and part of the story’s set-up. When the next faux-news bulletin came in, all hell started to break loose.

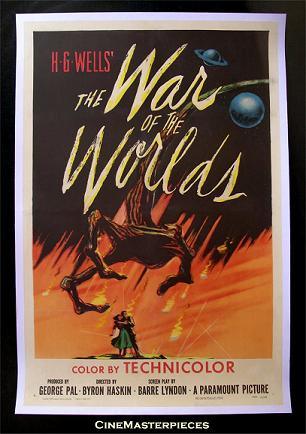

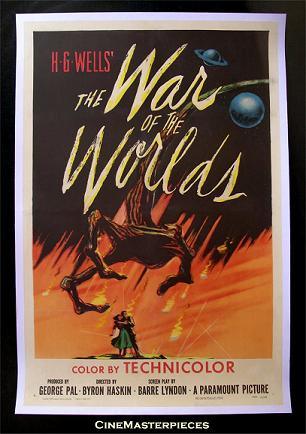

A poster for the George Pal-directed, best-known movie adaptation of WAR OF THE WORLDS (1953).

Oops.

But wait, that’s after the 15-minute-marker. It was only about 20 minutes before intermission and next announcement that this was fiction.

Yeah, but that was still after the announcement of the “evacuation instructions.”

Oops, again.

The New York Times reported, “In Newark, in a single block at Heddon Terrace and Hawthorne Avenue, more than 20 families rushed out of their houses with wet handkerchiefs and towels over their faces to flee from what they believed was to be a gas raid. Some began moving household furniture. Throughout New York, families left their homes, some to flee to nearby parks. Thousands of persons called the police, newspapers and radio stations here and in other cities of the United States and Canada, seeking advice on protective measures against the raids.”

Things were worse in Concrete, Washington, when the power and phones went out with disturbingly convenient timing with the radio play’s unfolding narrative.

Future TONIGHT SHOW host Jack Paar was on-air at Cleveland’s WGAR. As panicked listeners called the studio, Paar attempted to calm them on the phone and on air, “The world is not coming to an end. Trust me. When have I ever lied to you?” The listeners accused him of being part of a government cover-up.

One of the lessons of that night was the dangers of the malleability of the public in the hands of a powerful mass media. This was an early lesson, but not the first. On the other side of the ocean, Germany’s leader, Adolph Hitler, had already spent years successful molding the will of millions with media propaganda no more honest than a deliberate hoaxes like ALTERNATIVE THREE (1977), GHOSTWATCH (1992) or ALIEN AUTOPSY (1995) but far more effective than any here listed. Effective to the point of permanently altering the course of human history. One can hear Hitler gloating as he cited the panic as “evidence of the decadence and corrupt condition of democracy.”

One last note: If you read about this incident today, you will likely be reminded by the writer that WWII would erupt just months after the broadcast. Most American writers of this subject are myopic to the point of error and trivialization. You see, by the time of the broadcast, the Nazis had already intervened in the Spanish Civil War, Germany had already taken Austria, Italy had already taken Ethiopia, etc, etc. For tens of millions in Europe, the war was already underway; and most of the panicked Americans didn’t think we were being invaded by Martians, but Germans.

Editor’s Note: Robert Emmett Murphy is based in New York. This article is number 52 in a series of 100 essays he is penning, inspired by the British documentary THE 100 GREATEST SCARY MOMENTS (2003). It is reprinted with permission. The moment selected for the list can be found at the 1 hour, 36 minute marker. Listen to the entire original broadcast of WAR OF THE WORLDS here.

INVADERS FROM MARS – 1953

INVADERS FROM MARS – 1953

for David as everyone he turns to for help has already become “the enemy.” Eventually, he is believed by social worker Carter and astronomer Franz who rally the troops to assault the alien invaders.

for David as everyone he turns to for help has already become “the enemy.” Eventually, he is believed by social worker Carter and astronomer Franz who rally the troops to assault the alien invaders. effects nicely. Supplemental materials are abundant with featurettes on the restoration, interviews with Hunt and others, a round table style discussion with film directors John Landis, Joe Dante, editor Mark Goldblatt , special visual effects artist and two time Oscar Winner Robert Skotak (foremost expert on the film), and enthusiast and film preservationist Scott MacQueen, and much more including a twenty page booklet written by MacQueen. My copy even came with a pin-back button of the head (literally) Martian!

effects nicely. Supplemental materials are abundant with featurettes on the restoration, interviews with Hunt and others, a round table style discussion with film directors John Landis, Joe Dante, editor Mark Goldblatt , special visual effects artist and two time Oscar Winner Robert Skotak (foremost expert on the film), and enthusiast and film preservationist Scott MacQueen, and much more including a twenty page booklet written by MacQueen. My copy even came with a pin-back button of the head (literally) Martian!