Indie horror movies typically don’t get theatrical runs, but THEY REMAIN (2018), opening at the Plaza Theatre on Friday March 9 at 9:30 p.m., is that rarer bird in that it’s arriving with some serious critical buzz from media outlets as The Daily Beast and The New York Times. It’s based on the novella –30– by Laird Barron, an author at the head of the pack of a mounting Weird literary movement that’s been steadily creeping onto the little and big screens from TRUE DETECTIVE to ANNIHILATION (2018, in theaters now), adapted from the best-selling novel by Jeff VanderMeer. And even its leads, really its two characters, are risk-taking—a black man (William Jackson Harper of THE GOOD PLACE TV series) and a woman (Rebecca Henderson, APPROPRIATE BEHAVIOR [2014] ).

The plot is simple and increasingly unsettling. Keith and Jessica, who once were romantically involved, are assigned to investigate some strange animal behavior on land which once was the stomping ground of a Manson-style family cult. Isolated together in a compound reminiscent of PHASE IV (1974)—yes, there’s some eerie insect action, too—their sanity seems to be increasingly on edge. A festival circuit hit, THEY REMAIN premiered at the H.P. Lovecraft Film Festival in Portland, Oregon last October to a packed house and thunderous applause.

We caught up with THEY REMAIN Director/Screenwriter Philip Gelatt, no stranger to intelligent Sci-Fi Weird with the film EUROPA REPORT (2013) also under his belt, to find out more.

ATLRetro: What’s the secret origin story behind THEY REMAIN? Why did you want to adapt -30- and how did the project get off the ground?

Philip Gelatt: The secret origin story is basically that at the time I optioned the story, I was coming off the back of a string of failed screenplays. Things I’d written for producers who then just abandoned the projects and generally treated both the material and my work on it with a kind of Hollywood-ish disrespect. So I was feeling a bit pissed off, I guess. Both at screenwriting as a pursuit and craft, and at the industry as a whole.

So I went looking for something that I could do that would let me break all of my most hated rules of screenwriting. I also wanted something that fit my intrinsic tastes, which are a bit esoteric and cantankerous. -30- fit that bill perfectly. It’s a Weird story and a weird story. It’s elliptical and ambiguous and difficult, in the best way. I read the story a few times, just to be sure that I really wanted to try to tackle it. Then I sent it over to the producers who had worked with me on my first feature,THE BLEEDING HOUSE (2011). They read it and immediately saw the potential in it. And things just moved from there.

What were your greatest challenges in getting THEY REMAIN to the screen? Fundraising is always difficult for filmmakers, but was it harder raising funding for a Weird horror film?

We had myriad challenges, as almost all films of any level do. And yeah, fundraising was one of them. We sent the script out to various financiers, almost all of them passed. The typical story, y’know. In that process, we got responses that asked for the script to be changed in order to fit a more standard horror film. But to do that would have been to remove the very things that make it special and those notes didn’t come with a guarantee of financing. I was lucky in that the lead producers on the film had a bit of money; we were hoping we could get the budget up higher by bringing outside financiers on, but, in the end, we weren’t able to and we had to shoot with what we knew we had.

Can you talk a little about casting the film and working with William Jackson Harper and Rebecca Henderson?

Absolutely. I don’t like the auditioning process. I find it awkward and un-useful. It feels like you’re bringing actors in and putting them in front of a firing squad and I hate that. So, instead, I had prospective actors read the script and then I brought them in to have a conversation about the material and the characters. Ultimately, what I was looking for was people that had strongly engaged with the script, people who had ideas about the story, and people with whom I thought I could collaborate closely.

Filmmaking, despite what auteur theory might lead a person to think, really is all about choosing the right collaborators. Especially on this budget level. You need people you get along with and people who will challenge you and people who are dedicated to the film. Auditioning won’t let you see if an actor can be those things.

We cast both Will and Rebecca through that process. I then made the rather bold—and potentially stupid—decision to not really rehearse prior to shooting. My thinking was basically that by dropping the actors in on day one and just going, it would put them in the same mindset as the characters. Rehearsals would have given them a chance to grow comfortable with the material and each other… I figured better to try to keep it a little more raw than that.

I can’t say enough great things about both them. They handled every weird twist of that script with absolute professionalism.

The film’s visuals are key to building the mounting set of dread, so it works upon the audience as much as the characters. Can you talk a little about the look you wanted to achieve, connecting ambiance and lighting with mood, and cinematographer Sean Kirby, who has a strong background in documentary filmmaking?

This is, above everything else, a film about a certain mood and tone. The idea was to place the audience in the same position as the characters, so that as the film progressed they were grappling with the same frustrations and the same growing sense of dread.

There was a running visual idea that shots should always be slightly off. Sean called it “leaving room for the other in the frame.” Often that meant framing such that the human character is minimized or off center or, occasionally, almost completely hidden.

One of my favorite moments in the film comes fairly early, it is a shot with tree in focus in the middle of frame and, in the near distance behind it, out of focus, Keith is sitting and watching. It’s a rather long shot. We never rack-focus to Keith or highlight that he’s there. But he is. That to me is the essence of the film: you’re being asked to look closer.

Sound also is integral to the effect. What instructions did you give composer Tom Keohane and how did you both collaborate?

Tom and I worked pretty closely throughout the whole process of the film beginning in pre-production. I had him read the script and the story and compose music just based on those. This was before we’d shot anything. I wanted his initial musical response to the story. And some of that music lasted all the way to the final cut. It certainly helped inform the way editing process.

In terms of the actual scoring process once the film was shot, we had pretty long conversations about what might or might not work. For a time, we were trying a sound that was almost like Vangelis’s work on Blade Runner (1982). Very science-fiction and very big.

We pursued that awhile but ended up finding that it was misleading… it made the film feel too much like it was going to end up having robots or spaceships or something. And of course, it doesn’t have those things. So we pulled back and started investigating sonic textures for interior spaces and exterior spaces, and musical themes for each of the characters in the film. So much of the film is off-screen; we thought it was important to have certain musical cues as to what unseen element might be at play in any given moment. I’m very happy with how it turned out. For those interested, Tom will be putting the soundtrack up on Bandcamp.

Film and the written word are different media with different demands and strengths. The original story was set in a California desert, but you’ve re-set it to the woods—both of which can be very isolating locales. Some readers may wonder about the reason why you made this shift?

The basic reason we shifted it is a very boring one: budget. We knew pretty early that we weren’t going to be able to mount a production in the high desert. And we also knew that we had access to a sizable piece of land in upstate New York.

At first, I was a bit disappointed that we needed to make that change. I certainly started out picturing the story in the desert. But once I’d spent some time on the land where we were going to shoot, I got used to the idea and even started seeing some of the advantages in it in terms of color. A lot more hues and tones in the forest than the desert. And Sean and I did our damnedest to make that forest feel as strange and isolating as we possibly could.

Horror film is known for its jump-cuts and sudden scares, but THEY REMAIN’s horror is embedded in subtle unsettling moments. Do you have a favorite—or one that has been particularly gratifying to see the audience response to, without giving away too many spoilers?

Oh I’m pretty proud of a lot of moments in the film. I’ll list a few.

There are two times in the film that Keith wakes up and finds Jessica standing next to his bed. The first time it happens is one of my favorite moments in the film. Her performance there gives me chills.

Speaking of Jessica, the careful viewer will notice that she looks directly into the camera a few times over the course of the film. It’s quick but I think, even if you don’t pick up on it consciously, you do register that something strange has just happened.

Then there are a few sound details that I love. Early in the film, there’s a moment where we cut to black. And then the sound of two knocks brings us out of the black and into a new scene. That knocking sound is, of course, the sound of knocking on the hatch, something that becomes significant later in the film.

Interwoven, ominous details like that are the thing I most wanted to play with in constructing this film.

Maybe we’re a little partial because we know artist Jeanne D’Angelo’s work, but that’s also one hell of a movie poster—leaves surrounding a voyeuristic eye. Did you make suggestions to Jeanne, or how did that evolve?

Maybe we’re a little partial because we know artist Jeanne D’Angelo’s work, but that’s also one hell of a movie poster—leaves surrounding a voyeuristic eye. Did you make suggestions to Jeanne, or how did that evolve?

I love Jeanne’s work so much. Like with Tom, I actually approached Jeanne before we shot the film and hired her to do a piece of concept art that featured the skull and the horn and the forest.

So when the film was completed, she seemed like the obvious person to approach about doing a poster. I don’t remember making initial suggestions to her; instead she started doing sketches with her ideas for how it might look. And eventually we settled on the leaves and the eye and subtle details.

That poster feels so much like the film to me. She did an amazing job.

How do you feel about a theatrical release? Was it always a goal, or did you think this was just going to be festival circuit to DVD/streaming—the usual fate of many indie horror films?

It was always the goal. Sean shot the film to be seen big. And I wanted to make a movie that would benefit from the theater-going experience where viewers aren’t so tempted to check their phones or computers or get distracted. It’s a film in which you’re supposed to get lost… much easier to do that in a theater. I’m so grateful that we’re getting even a limited theatrical release.

The genuinely Weird movie is a rarity. What are a few Weird films that inspired you or are personal favorites and why?

I have a tendency to detect The Weird in the nooks and crannies of films that might not be commonly seen that way. So, for example, I believe THE SHINING (1980) to be a Weird film. Yes, it’s a haunted house film, but the ways in which the details of the story don’t add up, the way in which it frustrates interpretation, the psychology of it… those things feel deeply Weird to me.

I think Polanski’s film THE TENANT (1976) is a Weird film in the way it plays with identity and indulges in a very unsettling sense of the surreal. There’s no cosmicism in it but Polanski does kind of construct a twisted pantheon of god-like humans who destroy his character’s life. And then there’s the matter of the hieroglyphics on the bathroom wall…

Oh and here’s another outside-the-box pick: Peter Greenaway’s THE DRAUGHTSMAN’S CONTRACT (1982). It’s a movie I adore… and on its face it is basically a period piece murder mystery. But there is also this living statue that haunts the edges of the frames, never really acknowledged by any of the characters.

Is there any question no one has asked you yet about THEY REMAIN that you’re surprised by or would particularly love to answer? And what is the answer?

Hmmm… to their credit, people have avoided asking me questions like “what does the film mean?” Or “what’s real in the film?” Of course, I think it’d be really boring of me to answer those questions. Engaging with those things is part of the fun of the film. Which is my roundabout way of saying: this is the type of film that should leave you a little perplexed. My hope is that it will spark debate about just what has happened and just what it might all mean.

What’s next for you as a filmmaker?

In terms of what I’m going to direct next, I have two projects that I’m developing currently. But I’m not sure when—or even if—either one of them will come to fruition. I have been doing a good deal of screenwriting for other directors recently. Mostly science-fiction material. Nothing I’m allowed to say much about but keep your eyes peeled.

I’ve also been working on a hand-animated, rotoscoped, psychedelic, sword and sorcery fantasy film. It’s titled THE SPINE OF NIGHT. I co-directed that with the lead animator on the project, Morgan King.

We shot the live action bits of it years ago and since then a team of animators has been working hard on it. It should, finally, be completed sometime late this year. That’s one for fans of FIRE & ICE (1983), HEAVY METAL (both the magazine and the film) and old school Conan. It is a really distinctive and amazing project and I can’t wait for it to get out there.

All photos courtesy of Philip Gelatt and used with permission.

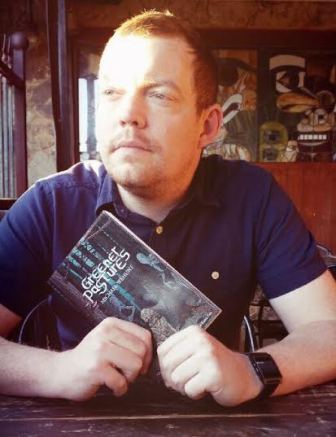

Atlanta author

Atlanta author  ATLRetro: What’s the “secret origin story” behind how you came to write THE STRANGE CRIMES OF LITTLE AFRICA?

ATLRetro: What’s the “secret origin story” behind how you came to write THE STRANGE CRIMES OF LITTLE AFRICA? What did you do to research the book, and what was the most challenging piece of information to find/fact-check?

What did you do to research the book, and what was the most challenging piece of information to find/fact-check? You still consider Atlanta home, though. Is that why you wanted your official book launch here at Charis? Can you tell readers a little about the festivities on Friday night?

You still consider Atlanta home, though. Is that why you wanted your official book launch here at Charis? Can you tell readers a little about the festivities on Friday night?