Lucas Hardwick

Contributing Writer

Welcome to Apes on Film! This column exists to scratch your retro-film-in-high-definition itch. We’ll be reviewing new releases of vintage cinema and television on disc of all genres, finding gems and letting you know the skinny on what to avoid. Here at Apes on Film, our aim is to uncover the best in retro film. As we dig for artifacts, we’ll do our best not to bury our reputation. What will we find out here? Our destiny.

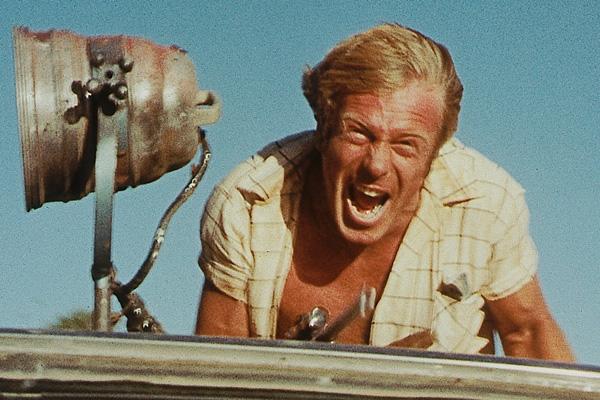

WATERWORLD – 1995

WATERWORLD – 1995

3 out of 5 Bananas

Starring: Kevin Costner, Dennis Hopper, Jeanne Tripplehorn, Tina Majorino

Director: Kevin Reynolds

Rated: Not Rated

Studio: Arrow Video

Region: 4K UHD Region Free

BRD Release Date: June 27, 2023

Audio Formats: English: Dolby Atmos; English: Dolby TrueHD 7.1 (48kHz, 24-bit); English: DTS-HD Master Audio 5.1 (48kHz, 24-bit); English: DTS-HD Master Audio 2.0 (48kHz, 24-bit)

Video Codec: HEVC / H.265

Resolution: Native 4K (2160p)

Aspect Ratio: 1.85:1

Run Time: 135 minutes

CLICK HERE TO ORDER

Children are the future, and what better way to impress upon them the horrors of the depleted ozone layer and melted ice caps in store for them than with a movie made exclusively for nine-year-old boys? Director Kevin Reynolds appeals to the swashbuckling MAD MAX-inspired tyke living inside all of us with his 1995 film WATERWORLD, placing the post-apocalypse on the high seas.

inside all of us with his 1995 film WATERWORLD, placing the post-apocalypse on the high seas.

Kevin Costner stars as “the Mariner” in this briny adventure, who after being outed by the nearest junk atoll community as a “Muto” for his “ichthy” qualities, finds himself on the run with a salvage dealer named Helen (Tripplehorn) and the little girl she cares for, Enola (Majorino). The trio is pursued across the flooded globe by a gang known as the Smokers, led by charismatic baddie Deacon (Hopper) who wants Enola for the mysterious tattoo on her back that is rumored to be a map that leads to the only remaining dry land on the planet.

Costner’s Mariner isn’t just a reluctant hero and custodian of the two stowaways needing his gigantic trimaran boat to get around, he’s brooding, and contemplative, and… kind of an asshole. What Mel Gibson did for the post-apocalyptic moody disposition, Costner turns into smug and unlikable. Part of the problem is we’re not sure what he really wants; he’s got gills. He’s got webbed feet. He can get to the earth’s drowned cities and plunder Davy Jones’s locker like any pro fish-man could. Outside of fending off scurvy (and why hasn’t he evolved out of that problem?) Mariner, with his enormous seafaring rig and its 50-caliber machine gun, is pretty well set for whatever the high seas throws at him. The only thing we know he wants is  these helpless women off his boat! It’s completely understandable that the film’s hero should have some advantages, but Mariner’s situation leaves him at the top of the food chain. Lack of incentive and Costner’s prickly, heavy-handed reluctance doesn’t do much to get us rooting for him.

these helpless women off his boat! It’s completely understandable that the film’s hero should have some advantages, but Mariner’s situation leaves him at the top of the food chain. Lack of incentive and Costner’s prickly, heavy-handed reluctance doesn’t do much to get us rooting for him.

Deacon and his gang of ruffians, while wildly more entertaining, also kind of have it made. They have jet skis; they have a cool hideout. They somehow have dry cigarettes and plenty of gasoline. And other than belittling his own people and making a few empty threats, Deacon doesn’t do anything inherently bad. He eventually gets around to kidnapping Enola, but he’s not even a creep about it. Dennis Hopper’s Deacon comes off more like a weird uncle who also just happens to be a high seas buccaneer. That’s not to say he’s not loads of fun to watch; Hopper (as is often the case in this film) delivers mundane lines like, “That’s why I love children: no guile,” with the relatable dryness of a man quietly frustrated after having just been insulted by a Smoker youth. Deacon wants to be the mustache twirling bad guy, but he’s ultimately just ineffective and comes off as downright lovable.

The narrative problems that plague WATERWORLD don’t prevent it from being the fun, daring adventure it wants to be. The overall swaggering tone of the film is often hampered, honestly, by Costner’s lack of any humor whatsoever. The scenes prominently featuring the actor consequently grind to a halt. The rest of the film seems to know exactly what it is, while Costner carries on like he’s paying the film’s $175 million production bill. Infamously known for not using a British accent in he and director Reynolds’ prior adventure film for nine-year-old boys, ROBIN HOOD: PRINCE OF THIEVES, Costner is a drag in WATERWORLD and proves that he’s best when portraying regular guys and baseball players.

Filming almost exclusively on water for the entire production is certainly not without intrinsic challenges. The enormous breadth of Mariner’s trimaran dictated the football field-size of the movie’s key atoll set and indebted Universal to pony up and extend Hawaii’s Kona Airport tarmac by a quarter mile to be able to accommodate the 747 tasked with delivering the titanic boat. The movie’s trimaran-sized costs along with tomes of bad and inaccurate press that included tales of people dying on set, ultimately affected the public perception of the film, suggesting that it was a problematic and troubled production. While rife with its share of challenges, troubles didn’t really occur until near the end of shooting when Reynolds dropped out of the picture due to creative differences with Costner, who took over as director and finished the film.

Arrow Video presents WATERWORLD on 4K Ultra High-Definition Blu-ray Disc. The three-disc boxed set is loaded with features that include three cuts of the film: theatrical, TV, and the extended “Ulysses” cut with shots and dialogue originally removed from the theatrical version. The set also includes the feature-length documentary “Maelstrom: The Odyssey of Waterworld,”—a terrific look at the making of the film by Ballyhoo Motion Pictures; the archival featurette “Dances With Waves;” and film critic Glenn Kenny’s exploration of the eco-apocalypse subgenre in the feature “Global Warnings.” This massive-sized limited release also includes a two-sided poster, collector postcards, and a 60 page booklet featuring  writing on the movie by David J. Moore and Daniel Griffith.

writing on the movie by David J. Moore and Daniel Griffith.

Where MAD MAX was a story of survival in a post-apocalyptic world brought on by oil shortage, the undercurrent of WATERWORLD and its characters’ odyssey for dry land attempts to serve as a warning regarding mankind’s destructive ways, but any sincerity for the film’s greater eco message is drowned out by its adventurous nature and self-awareness. Even the infamous and contextually relevant oil tanker Deacon and company inhabit seems pulled from a Mad magazine parody. Logic problems and Costner’s misguided intensity aside, the juggernaut that is WATERWORLD sets a course directly into our nine-year-old hearts.

Fathoms of fun that’s only inches deep. Recommended.

When he’s not working as a Sasquatch stand-in for sleazy European films, Lucas Hardwick spends time writing film essays and reviews for We Belong Dead and Screem magazines. Lucas also enjoys writing horror shorts and has earned Quarterfinalist status in the Killer Shorts and HorrOrigins screenwriting contests. You can find Lucas’ shorts on Coverfly. Look for Lucas on Twitter, Facebook, and Letterboxd, and for all of his content, be sure to check out his Linktree.

Ape caricature art by Richard Smith.