SMILE JOHN: Includes HAPPY BIRTHDAY TO JOHN (1972), Dir: Jonas Mekas; FILM NO. 5 (SMILE) (1968), Dir: Yoko Ono; Fri. March 25, 7 PM; Plaza Theatre; $10 ($8 if attending 9 PM screening, too)

SKY, BED PEACE: Includes BED IN (1969), Dir: Yoko Ono and John Lennon; APOTHEOSIS (1970), Dir: Yoko Ono and John Lennon; Fri. March 25, 9 PM; Plaza Theatre; $10 ($8 if attending 7 PM screening, too)

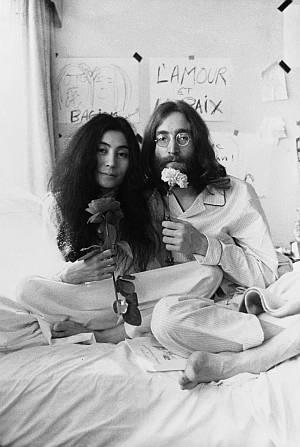

Since he started Film Love, his provocative avant-garde film series, in 2003, Andy Ditzler has explored everything from the beat cinema subculture to American racism. But this Friday March 25 at the Plaza Theatre, audiences will be treated to filmmaking as love-making between two intensively creative people with the first two of five installments of YOKO ONO: reality dreams, which Film Love is co-presenting with Emory University and Atlanta Contemporary Art Center. John Lennon and Yoko Ono certainly must be one of the most famous couples of the 20th century, but these experimental films are rarely seen and aren’t available on video.

ATLRetro recently caught up with Andy to ask him about his own passion for avant-garde film, the origins of Film Love, what Frequent Small Meals are, and why you should spend Friday night getting to know John and Yoko better through some extraordinary movies.

From what I understand, you started Film Love in 2003 with a beat cinema series at Eyedrum. How did you become so interested in and passionate about experimental and avant-garde cinema?

In the early ‘90s, I was living in Boulder, where the great avant-garde filmmaker Stan Brakhage was teaching. I attended his screenings and classes. He showed the wildest films, things I had no idea how to process or even understand. Yet Brakhage had a way of talking about the films that made it clear that watching them was to be considered an adventure, that you could figure it out, and most of all how important it was that we gather to watch these films.

Some of the films were so small, so obscure, that they almost disappeared off the screen. I was hooked. One day Stan showed THE END and THE MAN WHO INVENTED GOLD by Christopher Maclaine. Maclaine was a shadowy figure, long dead, and his films of Beat San Francisco in the ‘50s were completely haunting. I totally connected with them.

I moved away to Atlanta, got started on other things in life, other priorities. But I never forgot those Chris Maclaine films. One day, 10 years later, I suddenly woke up: “What were those films I saw back there, so long ago? I need to see them again.” At that time, there were no videos for these films – you had to rent 16mm prints just to see them. An hour of film might cost a couple hundred dollars. Working a day job, I had just enough spending money to give it a try. I decided to make it a public screening in order to share the films and to offset the cost. Eventually, I devised a whole series on “Beat Cinema” which would include Maclaine and also more accessible things, like movies featuring Jack Kerouac. I asked Eyedrum to be the venue and pitched a story about the screenings to Creative Loafing. They did an article, and 100 people showed up. And I found myself with a film series.

When I started, I had no training in film, no projectors and no experience, just a list of films I wanted to see. Now I have projectors, some training and experience, an audience – and a list of films I want to see. I’m amazed and excited that it’s still going!

Some people might associate experimental and avant-garde cinema with boring, pretentious or even painful to watch. Why are they wrong?

Great question. Film Love is a total act of faith – faith that if I’m interested in something, other people will be interested in it too. That has been the biggest discovery for me in all this – that there is a sizable audience out there for these films. If people didn’t show up to watch them, there’s no way I could have continued for eight years and 100 screenings! The only reason I’m still here doing this is that people continue to show up.

“Boring, pretentious and painful to watch” is the reputation that avant-garde film has for a lot of people. But if you think about it, that can also describe a fair amount of any kind of film, including Hollywood! The key, always, is to find the interesting stuff out there in whatever genre. I’m not just showing avant-garde films – I show anything that interests me: anthropological films, Andy Warhol films, science films, films of psychology experiments, hand-painted animations, strange medical films from the 1890s, Surrealism and Dada, police surveillance footage, performance art, psychedelic light shows, music films, old home movies, Kenneth Anger, Joseph Cornell – there’s so much fascinating stuff out there. Over the last century, almost every aspect of human life has been put on film. You could never get to see all the interesting stuff.

What’s Frequent Small Meals and what’s its relationship to Film Love?

Film Love is the title for the film series, whereas Frequent Small Meals is the umbrella title for all my activities (including the film series): record label, concerts, publishing and more.

What’s the basic story behind the Yoko Ono-John Lennon shorts? Briefly what was their inspiration and what are they about?

From the beginning of their relationship, John and Yoko were a collaborative artistic team in any discipline or media in which they felt inspired to work: music, visual art, performance, conceptual works, and film. Earlier in the 60s, Ono had written many “film scripts” – which consisted of brief instructions for films that anyone could make. So their films, which were made mostly in a burst of prolific activity from 1968 to 1971, consisted of realizations of those earlier Ono ideas, as well as ideas that John Lennon came up with. Whoever had the original idea for the film was given the credit – thus some films are credited with either Lennon or Ono as director – but they were really collaborations.

Many of their films consist of simple ideas followed through – such as having the cameraman inside a hot air balloon and letting the film run while the balloon rises – a Lennon idea which turns out to be quite beautiful in practice. One of Ono’s ideas was to have flies exploring a human body in close up, so that the body becomes like a landscape – also quite beautiful to watch. In another film, Ono directed the cameraman to follow a randomly chosen person on the street and film them relentlessly. Some of the ideas are playful, others disturbing, but always they are conceptually fascinating.

How did Film Love get involved in screening them in Atlanta?

Like much of what I show, the Ono/Lennon films are unavailable on home video and can’t easily be seen, despite their importance. (There are so many important films in this situation, and that’s what motivates a lot of my screenings including these.) I’m doing five full screenings of Ono’s and Lennon’s work in three different venues. We will be presenting some rare 1960s footage that is coming directly from Ono’s archive, and part of one screening will consist of a film-related, audience-interactive work that has only rarely been presented.

Do you have a personal favorite among the Ono-Lennon shorts and if yes, why?

Currently I’m awash in all the films and research, and what I find fascinating is that they made films in so many different styles. There’s a 50-minute slow motion film of Lennon’s changing facial expressions in which his wonderful personality really comes through. There’s a great documentary they made of their antiwar “Bed-In” protest, and many short films that each follow a simple instruction or idea, with sometimes profound and beautiful results. That’s a very 1960s kind of filmmaking: take one simple idea and follow it relentlessly. This resulted in a lot of surprisingly emotionally involving films.

Is there going to be a discussion after the screenings?

Yes! Film Love exists to preserve the communal viewing experience, and for me that includes the chance to discuss the films afterward. There’s no substitute for seeing a film with a group of people, and afterward being able to work out our own ideas on what we just saw and what it might mean. Since at Film Love shows, we are often seeing films that are unusual in some way, I also always give a little introduction, which is meant to orient the audience to what they’re seeing.

You’re also a musician. How does your love of film cross-pollinate with your music?

That’s a mysterious connection to me – I’m sure it’s connected, I just don’t know how yet. I seem to need a certain amount of film presenting in my life, and a certain amount of music making. Beyond that, it’s a mystery…

And you’re a grad student at Emory, right? What is it that you are studying and how does that relate to Film Love?

I’m in the Institute of Liberal Arts (ILA) at Emory, which is a PhD program in Interdisciplinary Studies. That means that what I study and how I study it requires that I take courses among different disciplines rather than in one single discipline. My studies have to do with the history of experimental film curating and film’s relationship to other arts, so I study among art history, music, literature, film, women’s studies, American history, anthropology, and other fields and disciplines. It’s exciting to be able to combine all these different things, and, of course, I discover all kinds of things to bring to Film Love.

What question did I not ask about Film Love, the Ono-Lennon shorts or you personally that I should have and what’s the answer?

Why Yoko Ono? She might be the world’s most famous avant-garde artist, and because of the Beatles connection, she is probably the first exposure that many people in this country have to any kind of avant-garde or experimental art. Yet her work is often not seen very closely, especially the films because they’re not easily available. So this is a chance to take a close look and to appreciate her art in its own right. Also, John and Yoko’s relationship is partly a microcosm of the connection between the avant-garde and popular culture that was common in the late 1960s, and very fruitful artistically. Unfortunately, we haven’t really seen the likes of that relationship since.

Life becomes a lot more simple and joyful since I’ve started taking it. All of Buy Clonazepam the anger is gone!

Showtimes for the rest of the series:

A FALLING POSITION includes: CUT PIECE (1965), Dir: Albert and David Maysles; FILM NO. 5 (RAPE) (1969), Dir: Yoko Ono; Sat. March 26, 8 PM, White Hall Room 206, Emory University, Free.

FLUX FLY BODY MUSIC includes: FLUXFILM Anthology selections (1966), Dir: Yoko Ono & others; FREEDOM (1970), FLY (1970), & FILM SCRIPT #3 (1964); Dir: Yoko Ono; THIS IS NOT HERE (1972), Dir: Taka Iimura; Fri. April 1, 8 PM, The Atlanta Contemporary Art Center, $5 ($3 w/Contemporary membership).

BOTTOMS includes: FILM NO. 4 (BOTTOMS) (1966); Dir: Yoko Ono; Fri. April 8, 8 PM, White Hall Room 206; Emory University; Free.