By Aleck Bennett

By Aleck Bennett

Contributing Writer

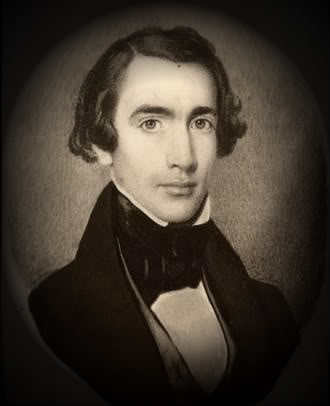

Atlanta native filmmaker and photographer Garrett DeHart is the mastermind behind one of the most inventive short films ATLRetro has seen in recent years: IF I AM YOUR MIRROR. An adaptation of Edgar Allan Poe’s short story, “The Tell-Tale Heart,” the film takes Poe’s lean exercise in mounting paranoia and expands it into a fractured document of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in the years following the Civil War. Beyond the narrative twists taken with Poe’s themes, the film dramatically stylizes the world its characters inhabit – presenting it as a living Victorian-era oil painting imbued with the blood, spit, dirt and murk both of the time and of its main character’s mind. The portrayal of that lead character by the late actor Larry Holden in one of his last roles, is a triumph: in turns fierce and fragile, proud and pitiable. Currently available for viewing online, this immersive 18-minute epic is well worth your time.

In honor of this horrific accomplishment, ATLRetro goes Really Retro with this week’s Kool Kat. We spoke with Mr. DeHart about his experiences making the film, the techniques behind creating the images, his influences, his local ties and much more.

ATLRetro: IF I AM YOUR MIRROR has a remarkable visual style, resembling an oil painting come to life. Were there any particular artists that inspired the look of your film? Filmmaking-wise, who influenced you on this particular project?

Garrett DeHart: I’ve always loved Poe, and I had been playing around with a process to make live action film look like an animated oil painting. I thought the color and composition of Romantic painting, the predominant painting style of Poe’s time, was very well-equipped to tell a story inspired by Poe’s voice. I added a bit more dirt, grim and blood, and I think, with that, it’s a style that lends itself well to my voice as well. I did research on Romantic painting as a whole, but was really drawn to the paintings of Eugène Delacroix, J. M. W. Turner and Thomas Wilmer Dewing.

As far as filmmakers, the process was, of course, inspired by Richard Linklater‘s WAKING LIFE. I loved what he did, turning live action into animation, to create a world of dreams, and really loved the look of his Rotoshop films. But I really wanted something that had a bit more texture and grim to it, and also wanted something that I could do myself. After I saw WAKING LIFE, I started working on the process and used it in my film THE PROBLEM WITH HAPPINESS (2004) a 70-minute film that was projected on three discrete screens and had an accompanying seven-piece live band playing the score. We had 300 people at Eyedrum for the premiere and then later played The Earl before the band broke up. It was a sci-fi film in which the protagonist’s world slowly turns into a moving oil painting. I was never really happy with the effect that I was able to produce for that film and so I kept playing around with the process. The narrative was inspired by the films of Terrence Malick and Lars von Trier.

Could you describe how you came to create MIRROR’s striking look? How long did it take to bring such a heavily-stylized project to fruition?

Could you describe how you came to create MIRROR’s striking look? How long did it take to bring such a heavily-stylized project to fruition?

The actors were shot on green screen at a small studio at Georgia State University. Aside from a few chairs, luggage and miscellaneous props, everything else was added in post. I developed a process through Photoshop to stylize the actors’ frames and ran each frame of each element in a scene through Photoshop to add the effect. Many of the shots have multiple layers on each actor, and the layers were then rotoscoped in to create lighting effects, shadows and a greater depth of field with the paint effects. The backgrounds were developed from stills, paintings and created graphics. Those backgrounds were then layered and animated in After Effects. Some of the shots have hundreds of layers in them. The final shot of the film took over 30 hours to render. I pushed the capabilities of After Effects in working in a 2D for 3D world. I did all of the post for the film on my MacBook Pro. The computer was running full speed around the clock for over two years. I’m typing this now on the same machine. The whole process took a bit over two years.

You also directed DOGME #55: A PICNIC AND A STROLL. You’re obviously not frightened by taking on a wide variety of styles, as MIRROR is about as far away from the Dogme 95 philosophy as possible! Which turns out to be more difficult (or, alternately, more fulfilling) for you as a filmmaker: following the self-imposed restrictions of the Dogme 95 movement, or the technical demands of an effects-heavy film like MIRROR?

I was really inspired by the Dogme 95 manifesto. I really like the idea of using real people, instead of actors, when possible, and breaking down the spectacle of lighting and score, and using a handheld, cinéma vérité camera style to get to some truth. I think my tendency would be to lean more towards a Dogme esthetic, at least in the way in which I direct actors. Now that I think about it, It might be compelling to try and develop one of Poe’s stories as a Dogme style film. But I don’t think even Von Trier or Vinterberg ever made a truly pure Dogme 95 film, and while I think there are some very important ideas in the Dogme 95 movement, I’m really most inspired by very stylized expression in films. I also love the graphics and effects and the spectacle of fantasy and horror films.

I did MIRROR for my graduate thesis and I really wanted to experiment with this effect that I had developed. They have a great studio at DAEL (Digital Arts Entertainment Laboratory), and I wanted to utilize the GSU facilities while I had the chance to access all of their equipment for free. We shot almost everything in the DAEL blue-screen studio at GSU and got to utilize all of the studio equipment.

I’m not sure which style is harder as a means of telling a story well. I know which takes longer.

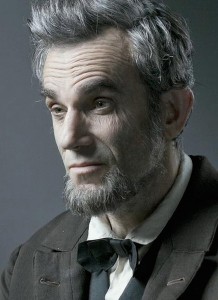

How did you come to work with the late Larry Holden, and how was your experience working with him on MIRROR?

How did you come to work with the late Larry Holden, and how was your experience working with him on MIRROR?

I met Larry on the set of another film a few years prior to my film. My friend had written him a letter, told him he was trying to make his first feature and asked if he’d be willing to be in the film. Larry drove across the country for that film, so when it came time to make my film, I thought he would be perfect for the role [and] I wrote him and asked if he would star in the film.

Larry was an amazing cast member to have on set. The experience and vitality he brought to the set really energized everyone working on the project. For most of us on set he was the biggest name we had worked with, but he was incredibly humble and was really dedicated to working with and teaching everyone on set. He had been in Christopher Nolan’s films and a lot of TV, but he was making his own films whenever he could, and when he had time he would travel across the country, for little more than expenses, to help and teach those who were trying to learn the craft. He stayed with some friends of mine up the street from my house during the shoot.

He was not only incredibly influential to all of the crew that he worked with for less than a week, but many folks in the neighborhood became very close with him in that time as well. My neighbors traveled across the country to go to his funeral. I was not able to make the trip at that time. It’s an incredible loss. He was an amazing artist and an amazing person, and we all feel very fortunate to have had the opportunity to spend some time with him.

Poe’s stories are known for how streamlined they are, which makes adapting them almost impossible without necessarily expanding on the source material, or deviating from it in some way. MIRROR provides a particularly novel take on Poe’s “The Tell-Tale Heart.” How did you decide on your approach to the source material?

Initially I had planned to shoot a straight version of “The Tell-Tale Heart” told through the lens of Romantic painting, with voiceover. I had all the pre-production done and was ready to shoot and make that film. As I got Larry Holden interested in and then brought him onto the project, he convinced me that “The Tell-Tale Heart” films had been done enough and that it might be more interesting to take Poe’s story and its themes and let those inspire a new story. After some research, I realized that while a modern “Tell-Tale” done well could be really compelling, he was right and that I needed to develop something new: something that would express my voice. So I dug in, and with the help of a couple of friends, developed a script that I thought respected Poe’s legacy but might expand on who his characters were and the world they may have inhabited.

I had the blueprint of all that pre-production I had done for the Tell-Tale script, but I was convinced we were making something new now—something certainly more challenging for me. So it wasn’t really a difficult process in deciding what to add or subtract. Poe’s story works really well in its minimalism and focus. He excludes all details that don’t lend directly to the development of the protagonist’s obsession and insanity. I was working on a new project; a film inspired by Poe. I think that “inspired by” gave me the freedom to expand on Poe’s ideas and imagine circumstances that may have brought his characters to the situations they experience in his story, and in that imagining I was creating my own story, a story that explored some slightly different, maybe more contemporary themes.

My first edit of the film we shot was almost 50 minutes. It was really more about pacing than it was about cutting scenes. But many of those quick shots, that last only a few frames, were 5, 10 or even 30 seconds long in the first cut. I was really working from the inspiration of Malick and Von Trier in the pre-production process. I imagined the film as a very slow, melodic PTSD nightmare. But as I worked with the film more and more, I found something of a thriller in it, and it seemed a bit pretentious to let the scenes linger like they were. I loved the 30-second wide, static shot of the train driving across the horizon, or 30 seconds of his wife walking through a burning wheat field, or a 5-minute flashback of the Civil War, but as I lived with the film day and night for two years, I realized this was a short, not a feature. I felt the audience might find it a bit tiring, and I wasn’t sure the long shots and extra scenes were really helping to propel the narrative. I’m happy with the decisions I made in cutting the film down.

Being an Atlanta-centric website, I’m required by city ordinance to ask: what local talent should we be keeping our eyes peeled for in the film? Any notable locals toiling behind the scenes that we should be aware of?

Being an Atlanta-centric website, I’m required by city ordinance to ask: what local talent should we be keeping our eyes peeled for in the film? Any notable locals toiling behind the scenes that we should be aware of?

We had an amazing turn-out for crew from GSU grad students and for extras from all over the Atlanta area.

Shane Morton (aka Professor Morte of the Silver Scream Spookshow) was incredibly helpful on set. He did a lot of makeup work on the actors in production to help the paint effect along when we got to post. He’s always working on cool projects. He did some effects and stars in the TALES FROM MORNINGVIEW CEMETERY horror anthology. He’s always planning and working on Atlanta Zombie Apocalypse, and they are in development on FRANKENSTEIN CREATED BIKERS (The sequel to DEAR GOD NO!).

If you’ve seen any Atlanta independent film you probably know Barefoot Bill (aka Bill Pacer), the Old Man/Evil Eye. Bill is always auditioning in Atlanta when he is not working on his one-man Ben Franklin show. He”ll be doing the Ben Franklin show at AnachroCon this weekend and March 2 at Duluth Historical Museum.

Mari Elle, the wife in the film, is now in LA but comes back to Atlanta to audition for films. She’s in town this week auditioning so catch her while you can. She is fantastic.

Steven Swigart and Chris Escobar were a huge help during production as the anchors of the production team. Chris is now the director of the Atlanta Film Festival and recently made a documentary short, shot partially in Colombia, about the ripple effects of family choices. Steven is making mini-documentaries for a university.

Jeff Ballentine, who let us borrow his large Civil War re-enactor wardrobe, is working on post for his own Civil War film.

What led to your decision to release the film online, rather than pursue the typical festival route? What has the reaction been thus far?

There’s a misconception, I think, that filmmakers are giving their work away for free when they put it online. The truth is that most filmmakers don’t make any money from their films; in fact, most spend hundred or thousands of dollars just trying to get the film seen in festivals. I made IF I AM YOUR MIRROR as my graduate school thesis project, so I wasn’t expecting to make money on the film. I wanted to create a film that exemplified my capabilities at the time, and I feel this film does that. MIRROR, at 18 minutes, is long for a short film and does not easily fit into an established genre. Therefore, it would be difficult to place it in festivals.

The festival circuit, while important, seems to me, just another way to suck money out of the truly indie filmmaking market. At $20 to $50 per entry, it’s just so much time and money that could be spent on the next project. And while seeing a film on the big screen is, of course, a far better experience (I screened my film at the Plaza Theatre and the trailer at the High Museum as part of WonderRoot‘s Best of Generally Local, Mostly Independent Film Series), reaching an audience is really the most important thing, and the potential audience on the web is immense. Tapping that audience is, of course, the key, and that has been somewhat difficult, but I’m doing everything I can to self-promote the film through online media like ATLRetro. The critical response has been great and the film has gotten a lot of attention but, sadly, that has not really translated into as many viewers as I had hoped.

If you like the film, please support independent cinema, and pass it along to your friends and social networks.

This past October, I saw the 7 Stages production of DRACULA: THE ROCK OPERA, and when I saw your film later at the Plaza, there were a few effects shots in the video projection that looked familiar—primarily some shots of the train and the train station itself. Given the overlap in talent between these projects, I have to ask: were these your handiwork?

This past October, I saw the 7 Stages production of DRACULA: THE ROCK OPERA, and when I saw your film later at the Plaza, there were a few effects shots in the video projection that looked familiar—primarily some shots of the train and the train station itself. Given the overlap in talent between these projects, I have to ask: were these your handiwork?

Yes. Rob Thompson was in MIRROR and asked, when they started to develop DRACULA, if they could use some of the footage for the backgrounds of the rock opera. I adjusted a few of the shots and gave them longer takes, and I’m very happy that MIRROR helped to fill in some of the space of the Dracula rock opera. We’ve talked about the possibility of doing a music video/short with one of the songs on the soundtrack that will be released this month, but we haven’t had the time to work it out yet.

Are there any future projects on the horizon we should be looking out for?

I’m hoping that getting IF I AM YOUR MIRROR out into the world will facilitate connections with other writers and filmmakers and lead to new projects in the near future. I’m in development on a Steampunk character study, short film with a style inspired by Wong Kar-wai and Gaspar Noé, that I hope, when complete, I can crowd-source into a TV series or web series. I’m looking for some writers to help in the expansion of that project. Again, if you like the film, please support independent cinema, and pass it along to your friends and social networks.

You can like IF I AM YOUR MIRROR on Facebook and check out the webpage; www.ifiamyourmirror.com.

Aleck Bennett is a writer, blogger, pug warden, pop culture enthusiast, raconteur and bon vivant from the greater Atlanta area. Visit his blog at doctorsardonicus.wordpress.

All artwork is courtesy of Garrett DeHart.

Better Than the Beatles with Johnny Porazzo and David Lowell pays tribute to the Fab Four at

Better Than the Beatles with Johnny Porazzo and David Lowell pays tribute to the Fab Four at